Home / Renditions / Publications / Renditions Journal / No. 45

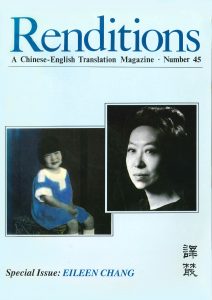

Renditions no. 45 (Spring 1998)

Eileen Chang

The work of Eileen Chang (Zhang Ailing) are featured in this special issue, including essays, stories, criticism, drawings and photographs.

152 pages

Table of Contents

| Editor’s Page | 4 | |

| Eileen Chang: A Chronology Compiled by Tam Pak Shan |

6 | |

| Reflections: Words and Pictures: excerpts Translated by Janice Wickeri |

13 | |

| ESSAYS | ||

| Dream of Genius Translated byKaren Kingsbury |

25 | |

| What Is Essential Is That the Names Be Right Translated by Karen Kingsbury |

28 | |

| Intimate Words Translated by Janet Ng |

33 | |

| From the Ashes Translated by Oliver Stunt |

47 | |

| A Beating Translated by D. E. Pollard |

58 | |

| FICTION | ||

| Love in a Fallen City Translated by Karen Kingsbury |

61 | |

| Shutdown Translated by Janet Ng with Janice Wickeri |

93 | |

| Great Felicity Translated by Janet Ng with Janice Wickeri |

101 | |

| Traces of Love Translated by Eva Hung |

112 | |

| ON EILEEN CHANG | ||

| Hu Lancheng | This Life, These Times: excerpts Translated by D. E. Pollard |

129 |

| Wang Xiaoming | The “Good Fortune” of Eileen Chang Translated by Cecile Chu-chin Sun |

136 |

| Lim Chin-chow | Reading “The Golden Cangue”: Iron Boudoirs and Symbols of Oppressed Confucian Women Translated by Louise Edwards and Kam Louie |

141 |

| Notes on Contributors | 150 | |

| Books Received | 152 | |

Sample Reading

The material displayed on this page is for researchers’ personal use only. If you wish to reprint it, please contact us.

From the Ashes

By Eileen Chang

Translated by Oliver Stunt

A fair distance now lies between myself and Hong Kong: several thousand miles, two years, new things and new people. At the time, my experience of Hong Kong at war was impossible to put into words if only because of the immediacy and the intensity. Now that the mind has calmed, the subject can at least be touched upon with some degree of coherence. However, my impressions of wartime Hong Kong are virtually all confined to irrelevant matters.

I have no intention of writing a history, and nor am I qualified to comment on the attitudes historians should take, but privately I have always wished they might concern themselves a little more with irrelevant matters. This thing we call reality is without structure, a confusion of gramophones playing in chaotic cacophony, each singing its own song. But amid the unintelligible clamour is the unexpected lucid interval that sours the heart and moistens the eye, a discernible melody instantly reclaimed by the weighty gloom, the spark of understanding swamped. Painters, writers, and composers intertwine fragmentary, accidentally discovered harmonies, and no attain artistic wholeness. But if history insisted on her own artistic wholeness, she would become fiction. For instance, H. G. Wells’ The Outline of History cannot rank as a proper history for the simple reason that the entire work is based on the conflict between the individual and society, and as such is just a shade over-rationalized.

Regardless of whether they were political or philosophical, world views which ware too clear-cut are bound to provoke antipathy. Man’s joie de vivre is solely to be found in life’s irrelevancies.

Back to Hong Kong. When we first heard that war had broken out, a girl in my dormitory started panicking.

“What am I to do? I’ve nothing to wear!”

She was a moneyed overseas Chinese who simply had to have a different wardrobe for every conceivable social occasion. And she was indeed fully prepared for anything from a junk party to a stately dinner. But she hadn’t anticipated war. In the end she managed to beg a big black quilted gown that most likely didn’t attract the attention of the squadrons circling overheard. When the time came to flee we all went our separate ways. I saw her once more after the war. She had her hair cropped and set in the masculine Filipino style which was all the rage in Hong Kong because you could pass for a man.

During the war, each of our psychological responses had some close association with clothing. Take Sureika for instance. She came from a remote village on the Malay peninsula. A real beauty, she was slender and dark-skinned, dreamy-eyed, and had gently protruding teeth. And as is the case of most girls who have received a convent education, she was disgracefully naive. She opted for medicine, which involved dissecting human bodies – “do the corpses wear anything during dissection?” Sureika was misgiven on this point and asked around. It soon became a standing joke around the university.

A bomb landed next to the dormitory, and the warden had to insist that we get down the hill and out of the way. Despite our predicament, Sureika had the presence of mind to sort out her brightest clothes and, ignoring the well meant remonstrations of lots of sensible people, she somehow managed to shift her cumbersome leather trunk down the hill in spite of the gunfire. She joined the defence effort as a supply nurse for the Red Cross, only to find herself squatting on the ground kindling firewood in her copper satin gown embroidered with green “longevity” characters. It was a shame but it was worth it. The dash she cut in her outfit gave her a new-found self-confidence without which she would have found it difficult to blend in with her male counterparts. They shared the same hardships together, took the same risks, enjoyed the same jokes, and as she gradually got used to them, she spoke up more and became more capable. The lessons of war would have been hard for her to come by otherwise.

As for the majority of students, our approach to the war, if I may draw an analogy, was like that of someone sitting on a hard bench trying to catch forty winks. He is uncomfortable and grumbles incessantly, but in the end he nods off.

Whatever it was possible to ignore we ignored altogether. Escaping with our lives, we were tossed about on a swell of kaleidoscopic experiences, but we were simply what we were, unsoiled, carrying on with our ordinary routines. There were times when our behaviour seemed abnormal, but on closer scrutiny, it was consistent enough.

Take Evelyn, for example. She was from China and had seen a war or two. She said herself that she could stand up to hardship, that she had become used to constant anxiety. But when they bombed the nearest military redoubt, she was the first to crack. She cried and fussed hysterically, and came out with all these horrific wartime anecdotes that turned the other girls pale. Her pessimism was, however, of a healthy kind. When our stocks of grain dwindled, she started eating far more than usual and urged everyone to do the same as there would soon be nothing at all. It had of course occurred to us that we should economize and perhaps start rationing, but Evelyn did all she could to sabotage everything. She would stuff herself and sit to one side and weep all day. It made her constipated.

We would assemble in the pitch-black luggage room in the dormitory basement, and all we could hear was the clatter of machine-gun fire, like rainfall on lotus leaves. So wary was our friend the little cook of stray bullets that she wouldn’t go anywhere near the window to wash the vegetables in the light, and our vegetable soup would be full of wriggling insects.

Of all my fellow-students, Fatima was the only one with any guts – she would defy death and go into town to watch cartoon in Technicolor. When we got back, she would go upstairs alone to wash. When a stray bullet shattered the bathroom window she simply carried on with her bath, calmly splashing about and singing, which infuriated the warden. Her indifference seemed to be a mockery of our collective fear.

The university closed down and overseas students had to leave the dormitory. But there was nowhere to go and no way to come by board and lodging without contributing to the defence effort, so a group of my contemporaries and I went along to the Air Raid Precaution headquarters. Having signed up and been issued with our badges, we left, only to run into the air raid. We leapt off the tram, ran for the pavement, and took shelter in a doorway in some doubt as to whether we had discharged our responsibilities as air raid wardens. (What were they anyway? The war was over before I came up with an answer.) The doorway was crammed with people, well wrapped up wintry people smelling of brilliantine. Looking out over the heads, we could see a clear light blue sky. An empty tramcar had been stopped in the middle of the road, pale sunlight shining on it, shining through it. There was a primeval desolation about this lone tramcar.

The thought of ending up dead among a crowd of strangers upset me. Still, would dying together with my family, being bombed to bits with my own flesh and blood have been any better? Someone shouted at us to “Get down! Get down!”. Not that there was any room for anyone to crouch in. All the same, crammed up against each other though we were, we did manage to crouch down. A plane dived and there was a bang directly above us. I hid my face in my warden’s tin hat. Everything went black for a bit before I realized we were still alive, that the bomb had come down across the way. A young shop-boy with a wounded thigh was carried in, trouser leg rolled up, bleeding a little. He was thrilled to be at the centre of attention. We in the doorway pounded on the door, which wouldn’t budge; by now, emboldened by our mission, we were clamouring in uproar,

“Open up! There’s a wounded man out here! Come on, open up!”

It was no wonder those inside wouldn’t, because we were a very motley crew, and could have got up to anything. Outside, indignation had given way to straight-out cursing and eventually they opened up. We all trooped in noisily. The ladies and their maidservants inside were shocked speechless. Afterwards there was no way of knowing whether any of the boxes and crates in the passage had gone missing. The planes persisted with their bombing, but the bombs fell farther and farther away. After the all clear sounded, everybody crowded recklessly on to the tram, worried only about being left behind and forfeiting the far.

We found out that our history professor Mr France had been shot – and that it was his own people who had killed him. He had been drafted like most other Britons. Dusk had fallen, and he had returned to the barracks, most probably so lost in thought that he hadn’t heard the sentry’s challenge, and the sentry opened fire.(1)

Mr France was a liberal sort. He was thoroughly sinicized – his Chinese characters weren’t at all bad (though he was never too clear on stroke order) – and he was a drinker. And he travelled up to Canton with Chinese colleagues to visit young novices in a nunnery of ill repute. He had built himself three bungalows in a sparsely populated spot, one of which was specifically for rearing pigs in. His home had neither electric light nor running water – he didn’t subscribe to material comfort. He owned a car, however – an old banger on its last legs that his cook-boy went to market to buy vegetables.(2)

He had the ruddy face of a child, porcelain-blue eyes, and a jutting spherical chin. His chair had begun to thin, and a faded scrap of silk around his neck masqueraded as a tie. He smoked like a chimney during lectures: even as he believed them, a cigarette constantly dangled precariously from his lips, bouncing up and down like a springboard, never dropping out. He would deftly toss his stubs window-wards, skimming the girls’ bouffant perms: something of a fire hazard.

His historical research contained some highly originally insights. And when it came to “establishment” writings he would put on hilarious displays of ornate oratory. He instilled in us his fondness for history and his bird’s-eye world views. We could have learned so very much more from him but for his death, and a most inglorious death it was at that. First and foremost, he hadn’t laid down his life for king and country. And even if it had been a case of heroic martyrdom, so what? He’d never shown much sympathy for British colonial policy, but then again he’d never been too bothered about it either, possibly because he knew the world’s follies wouldn’t end there. Every time the volunteers were to be drilled, he’d announce, drawling,

“I won’t be seeing you on Monday, young ones. I’ll be out on martial manoeuvres.”

We never imagined “martial manoeuvres” seeing this gentleman, this decent man, to his death. It was a real loss to humanity. …

The public amenities in our beseiged city were a total shambles, as many others have previously said. The cooling ducts of the government cold stores had fallen into disrepair, but they would rather have seen mountains of beef rot than bring the stuff out. Volunteers for the defence effort were allocated nothing but rice and soya bean rations. There was no oil and no fuel. In every air defence unit, the scramble for firewood and rice to keep those under its command nourished was so intense, there wasn’t the time to look out for bombs. I had nothing to eat for two days; I floated into work. Of course, it was only fitting that someone as half-hearted about the job as myself should have to put up with a little hardship. Amid the gunfire, I read the late Qing novel The Bureaucracy Exposed. I had read the book as a child, but hadn’t appreciated its finer points, and had ever since been wanting to reread it. As I read, I wondered whether I would be allowed to finish it. The print was minuscule, the light was bad, but if a bomb had dropped, what use would eyes have been anyway?

Throughout the eighteen-day siege, everybody had that horrible four-in-the-morning feeling – the shivering dawn, the confusion, the huddling up, the insecurity. You couldn’t go home. If you did, your home might no longer be there, the house could have been demolished, money could have become wastepaper in the blink of an eye, people could have died, and you were even less sure of living the day out. I’m reminded of two lines: “Aggrieved I bid my dear farewell, and drift off into hazy mists.” But somehow the lines don’t reflect the indifferent emptiness, the hopelessness. It was intolerable and, in a desperate bid to cling to something dependable, people got married.

One couple came into our office to ask the ARP branch director for permission to borrow a car to go and get their marriage certificate. The groom was a doctor who probably wouldn’t have looked too kindly under normal circumstances, but he kept gazing at his bride with an expression of love in his eyes that verged on grief. She was a nurse, petite and attractive, her rosy cheeks brimming with joy. She hadn’t managed to get hold of a wedding dress, and she simply wore a light green silk dress with a dark green border. They came in several times and waited several hours, silently sitting face each other, looking into each other’s eyes. They couldn’t help beaming at each other, and it caused us all to smile too. Indeed, they should be thanked for the unwarranted happiness they brought.

Eventually, the fighting ended. To begin with it wasn’t easy to get used to. Peacetime played havoc with our minds – it was like being drunk. Whenever we saw an aeroplane against a blue sky, we could be sure it wouldn’t drop a bomb on our heads as we gazed up at it in wonder, which was enough to render it perfectly lovable. Thin bleak wintry trees like pale yellow clouds, clear water flowing from the water pipes, electric light, the bustle of the streets, all these were ours once more. Most importantly, time was ours once more – daytime, night-time, the four seasons – for the time being we were able to get on with living and were, understandably, beside ourselves. This unique post war spirit must be why the 1920s came to be referred to as the “roaring twenties” in Europe.

After Hong Kong fell, I remember how we scoured the streets in search of ice cream and lipstick. We burst into every eating-house we came across to ask for ice cream. In only one were they forthcoming. They said there might be some of the following afternoon. The next day, we walked almost four miles to keep the appointment, and ate a whole plate of exorbitantly-priced ice cream full of crunchy ice shavings. And the streets were packed with stalls selling make-up, Western medicines, tins of beef and mutton, stolen suits, knitwear, lace curtains, cut glass, whole rolls of woollen fabrics. Every day we went into town to shop. We called it shopping, but in fact we did no more than look. I learnt then how to turn shopping into a pastime. No wonder most women never tire of it.

Hong Kong rediscovered the joy of eating. There was something truly strange about such a natural and basic function suddenly being given excessive attention, becoming vulgar and abnormal under the intense glare of the emotions. On the post-war streets, every five or ten paces immaculately dressed office clerks would be squatting by little burners, deep-frying rock-hard yellow biscuits. Hong Kong isn’t as quite as enterprising as Shanghai, and speculative ventures are slow to catch on. For an absolute age, the street food was monopolized by these little yellow biscuits. In time people experimented with buns, samosas, and suspicious-looking coconut cakes. Schoolteachers, shopkeepers, legal clerks – there was a mass career move into the art of confectionery.

Once, we were standing at the end of a stall eating sizzling hot turnip cakes and within just feet of us – so close we were virtually stepping on them – lay the purplish corpses of the destitute. Would a Shanghai winter be anything like as cruel? At least that city wouldn’t be quite as blatantly approving. Hong Kong hasn’t the decency of Shanghai.

There was no petrol. Garages were converted into eateries and there wasn’t a draper or herbalist who wasn’t selling cakes on the side. Hong Kong had never been so gluttonous. In the dormitories, the sole subject of conversation was food.

In this euphoric atmosphere, Jonathan stood aloof, alone, disdainful and resentful. He was an overseas Chinese who had joined the volunteers and had seen action. He wore an open-necked shirt under his greatcoat, and his wan complexion and the lock of hair dangling between his eyebrows suggested Byron. Sadly, he suffered from a heavy cold. Jonathan knew what fighting on the Kowloon side had been like. What angered him most was the way they had sent two undergraduates out of the trenches to carry a British soldier back –

“Two of our lives aren’t worth one of theirs. When we were recruited, we were promised special treatment – we were to be under the command of our professors. Well it all amounted to nothing.”

When he relinquished his pen for the sword, he must have thought fighting would be a bit of a YMCA outing to Kowloon.

After the ceasefire, we worked as nurses in the makeshift hospital in the university. Apart from a few patients from the main hospitals, the rest were either coolies who had been caught in the crossfire, or looters who had been injured during arrest. There was a TB sufferer with a bit of money who got another patient to wait on him. he sent him out on errands, running about the streets in a standard issue floppy-sleeved hospital gown. An incensed hospital chief thought this most improper and expelled the two of them. There was another who was discovered to have concealed a bandage, several surgical instruments, and three pairs of hospital trousers under this mattress.

We didn’t get much comic relief of that sort. The patients’ days were tryingly long. The powers that were ordered that they comb rice for grit and bits of grass. And because there really was nothing else for them to do, they seemed quite content with such monotonous work. Over time, they developed a bond with their wounds. Different wounds came to represent entire personalities. I applied ointment and changed dressings daily, and I was aware of eyes gazing lovingly at the regenerating flesh with an almost creative fondness.

They were put up in the boys’ dining-room. The room had always been total bedlam, with the Brazilian love songs of Carmen Miranda on the wireless, and the boys breaking crockery and cursing kitchen hands at every turn. But now the place was home to thirty-odd silent and restless smelly people whose legs were incapacitated, and who were incapable of using their brains because they weren’t in the habit of thinking. We hadn’t enough pillows, so we pushed their beds up against the pillars for them to prop up their heads, their necks at right angles to their bodies. and there they would lie, wide-eyed, awaiting two daily meals of brown rice, one dry, one gruel. The sun would shine on the glass doors, their pasted-on paper strips of shatter-proofing torn and weather-beaten into irregular white shreds like paper witches. In the evenings these grotesque and ghoulish silhouettes would appear against the dark blue panes.

Even though they were extremely long at ten hours, we didn’t mind the night-shifts because there was very little to do. If patients had to relieve themselves, we’d just go out and call an orderly. “Bed-pan for number twenty-three.” Or “Jerry for number thirty.” We’d sit behind the screens reading, and they even gave us bread and milk as a midnight snack. Our only regrets were the deaths. Eight or nine times out of ten, they came during the small hours.

One patient had an evil-smelling gangrenous sacrum. When the pain became acute, the expression on his face was almost ecstatic – eyelids slack, his mouth drawn back in a smile suggesting an unscratchable itch. He’d call out all night long “Hey Miss! Hey Miss!” in long drawn out, quivering tones. I’d ignore him. I was an irresponsible and heartless nurse. I hated this man because his suffering eventually woke the whole ward. They couldn’t ignore him, and they all called out “Miss!” in unison. I had no choice. I stood sullenly at his bed.

“What do you want?”

He thought for a moment, then groaned, “Water.”

All he wanted was to be waited on – literally anything would have done. I told him there was no boiled water left in the kitchen and left him. He sighed and quietened down for a moment before starting up again. His voice wasn’t up to him but he still kept moaning.

“Hey Miss … Hey Miss … Hey … Hey Miss … “

It was three o’clock. My colleague was napping. As I went to heat the milk, I steeled myself and threaded my way through the ward and down to the kitchen, carrying the fat white bottle. By then, most of the patients were awake, gazing helplessly at the bottle that was more beautiful in their eyes than an unfurled lily.

Hong Kong had never had such a cold winter. I soaped the lidless copper pan down, the pain in my hands slashing like a knife. the pan was caked with grease and grime. Domestic staff simmered soup in it, patients scrubbed faces in it. I poured the milk in. The copper pan was perched over the blue gas flame, a bronze Buddha on a blue lotus, pure and radiant in tranquil resplendence. But the nagging “Hey Miss!” drawl tracked me down to the kitchen. A white candle was the only light in the tiny room. I brought the milk to the boil, flustered and enraged as a hunted beast.

The day he died was one of rejoicing for all. Day was about to break. We left the burial matters in the capable hands of experienced professional nurses and retreated to the kitchen. My colleague had baked an ovenful of buns with coconut oil. They tasted similar to Chinese fermented-grain biscuits. Cocks were crowing on another clear and frosty morning. We, the selfish, carried on living as if nothing had happened.

Apart from work, we learned Japanese. A young blond crew-cut Russian had been appointed to teach us. In the classroom he would usually ask one of the girls her age in Japanese. If she didn’t answer at once, he’d speculate.

“Eighteen? Nineteen? Surely you’re not a day over twenty? What floor are you on? Shall I come and visit sometime?”

She’d be thinking of how to decline, and he’d grin and say, “No English. The only Japanese you know is ‘Come in! Will you sit down and have something to eat?’ You don’t know the Japanese for ‘Get lost’.”

His little joke over, he’d be the first to blush. His lessons had originally been bursting with students, but attendance had begun to dwindle. Eventually numbers were embarrassingly low. Indignant, he stopped coming, and a new teacher was brought in.

The Russian had been to see my sketches, and had taken a liking to only one of them, a portrait of Fatima in a slip. He was willing to shell out five Hong Kong dollars for it. When he saw our reluctance he quickly explained.

“Five – without the frame, that is.”

The peculiar wartime atmosphere inspired a lot of sketches. Fatima coloured them in. I myself looked upon these works in wonder and amazement, and while that might seem immodest, I know for a fact that they were good. They didn’t look anything like my drawings, and I later gave up trying to produce anything as good. Regrettably people found them rather puzzling. But even if the energies of a lifetime were to be spent composing biographies by way of annotation for those rows of many and various heads, it would be worth it. The cantankerous landlady whose crossed eyes stuck out like a pair of taps; the young wife whose neck and head could have been the blow dryer at the hairdresser’s; the prostitute with her contagious diseases, squatting like a lion or a dog, garter belt and red silk stocking tops showing beneath her clothing.

I am particularly fond of the colours Fatima used for one of the pictures, all different blues and greens. They call to mind “mermaids in the green sea shedding pearl tears on a moonlit night, jade in the blue hill exuding mist in the warm sun”.

Even as I drew, I knew that whatever ability I had would soon be lost. This in itself taught me a lesson that has stood the test of time: if you feel like doing something, do it then and there or it may be too late. “Man” is such an unpredictable creature.

A youth from Vietnam had a minor reputation among the students as something of an artist. He complained of his brushwork being less bold since the war. He’d been cooking his own meals, which had weakened the muscles in his arm. It pained us terribly to see him frying his daily aubergines (he only knew the one aubergine dish).

When the war broke out, most Hong Kong University student jumped for joy. Our end of term exams so happened to start on 8th December and the undue exemption was a godsend in a million. But all in all we endured a fair amount that winter and ended up with a better idea of where our priorities lay. But it’s difficult to be sure of what “priorities” actually are . . . once you cut through the waffle, two things alone appear to remain: food and sex. Human civilizations have sedulously sought to break the bounds of a simple and brutish existence. But haven’t the efforts of recent millennia ultimately been in vain? That is the reality of it. Hong Kong’s overseas students were stranded there with nothing to do but shop for food, cook, and flirt all day long. But it wasn’t the ordinary flirting of students – none of the mildness laced with sentimentality. After the war, boys would like on their girlfriends’ beds playing cards long into the night. Early the next day, before she’d woken, he’d be back, sitting on the edge of her bed. Through the walls you’d hear her squealing coyly “No! Stop it! No, I won’t!”, and not until she had got out of bed and dressed would it stop. It was a phenomenon which provoked different reactions in different people – whether anyone retreated to Confucius’s side in horror is as may be. At the end of the day, a measure of restraint is indispensable. Primitive man is indeed innocent, but “humanly” speaking he is incomplete.

The director of the hospital was much concerned by the possibility of “war babies” (illegitimate children conceived during the war). When one day he caught sight of a girl smuggling an elongate bundle out of the dormitory, he was convinced his worst nightmare had come true. Only later did he learn that she had been taking out the rice she received for working to exchange for cash. Because there were so many thugs on the streets she had been scared of being mugged, and had disguised her bag of rice as a baby.

The eighty-odd youngsters assembled there had escaped the jaws of death and, for that very reason, they were all the more spirited: they were fed and housed, and worldly pleasures weren’t there to distract; there were no teachers (the truth is that most of the teachers simply weren’t missed), but there were lots of books – pre-Han philosophy, The Book of Songs, the Bible, Shakespeare – an ideal environment in which to pursue one’s university education. However, my fellow-students saw it all as a tedious time of transition: the traumas of the war were in the past, and the future would see them sitting whimpering on their mothers’ laps relating their miseries, releasing tears log pent up. For the time being they had to make do with scrawling the words “Home Sweet Home” all over filthy windows out of boredom. Though getting married out of boredom was pretty pointless, there was still something positive in it.

Those without work or other pursuits often resorted to an early marriage – the overcrowded engagement columns of the local papers were proof of that. Some of those tying the knot were students. They would only have had an elementary understanding of human emotions, and as soon as the earliest opportunity to scratch the surface of someone arose to reveal a timid, vulnerable, pitiable, laughable man or woman they would fall in love with discovery. Of course they had everything to gain and nothing to lose by love and marriage, but such a voluntary narrowing of their horizons at an early age was truly a tragedy.

And the vehicle of life rumbles on. As we travel on it, we may go no further afield than the odd familiar thoroughfare, but the glow of flaming skies will still stir the soul. More’s the pity that we preoccupy ourselves with searching for a reflection of ourselves in a passing shop window – only to see faces, our own faces, pallid, paltry. In our self-centre vacuity, in our smug, shameless stupidity, we all resemble each other. And each of us remains alone.

___________

(1) According to the other students at the time, N.H. France suffered from claustrophobia and deliberately brought about his shooting to avoid confinement.

(2) France was well-known for riding to work on a donkey.