Home / Renditions / Publications / Renditions Journal / No. 75

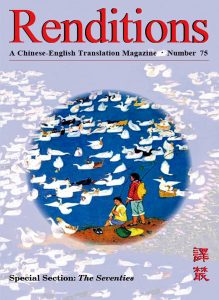

Renditions no. 75 (Spring 2011)

Special Section: The Seventies

This issue focuses on a set of translations from the collection of reminiscences edited by Bei Dao and Li Tuo, The Seventies. A compendium of writings on their experiences of the decade that has proved so pivotal to contemporary China by a large group of writers who lived through it, the work has attracted great attention in the Chinese-speaking world. Also included is a prizewinning translation of the first three chapters of Mao Dun’s Waverings, at once the second novella of the Eclipse trilogy, the author’s first venture into prose fiction and a key document of the 1927 revolution.

135 pages

Table of Contents

| Editor’s Page | 5 | |

| Special Section: The Seventies | ||

| Theodore Huters | The Seventies—Introduction | 9 |

| Li Tuo | Preface

Translated by Theodore Huters |

12 |

| Xu Bing | Nourished by Ignorance

Translated by Richard King |

22 |

| Bei Dao | Out of Context

Translated by Theodore Huters |

47 |

| Huang Ziping | Practical Linguistics of the 1970s

Translated by Nick Admussen |

72 |

| ———— | Eight Song Quatrains Translated by Philip Watson |

89 |

| Mei Yaochen: Encountering Rain in the Mountains | ||

| Sima Guang: Strolling Alone to the Marge of the River Luo | ||

| Qin Guan: Spring Day | ||

| Lu Meipo: Snow and Prunus | ||

| Yang Wanli: Plum Blossom in a Little Vase | ||

| Lu You: When I was twenty I wrote poems for chrysanthemum pillows which were widely circulated. This autumn I happened once again to be picking chrysanthemums to sew into a pillow bag, and felt sad. (No. 2) | ||

| Jiang Kui: Passing Deqing (No. 2) | ||

| Xie Fangde: The Shadows of Flowers | ||

| Mao Dun | Waverings: excerpts

Translated by David Hull |

97 |

| Book Review | 128 | |

| Notes on Authors | 131 | |

| Notes on Contributors | 134 | |

Sample Reading

The material displayed on this page is for researchers’ personal use only. If you wish to reprint it, please contact us.

Nourished by Ignorance

By Xu Bing

Translated by Richard King

……

In a place this remote, the old ways still hold true. The first time I ever saw Huangjin wanliang [ten thousand ounces of gold] and zhaocai jinbao [bring in wealth and treasure] written in the form of a single character, was not in some work on local customs, but on the sideboard in the Party secretary’s house. I was amazed by it, an amazement that you couldn’t get by reading about it in a book. At weddings and funerals, a further aspect of the villagers’ ‘mentality’ would be revealed. For funerals, they make all manner of things with papier mâché, just like a folk version of Second Life. The old people would leaf through a few papers, and basing themselves on the strange characters written there, they would copy onto a strip of white cloth to make into banners for use in funerals. Later on, when they found out that I could do calligraphy, and had the proper ink for it, they would get me to do it. Subsequently I did some research and I found out that this was called ‘mystic scrawl’, and that it was a writing system for communicating with the spirit world. The principal manifestation of my importance in the village was that every time there was a wedding, they would ask me to go and decorate the bridal chamber, not because I had any abilities in installation back then, but because my family had what was traditionally called a ‘full house’, comprising mother and father, elder brother and sister, and younger brother and sister. If someone like that makes up the bridal bed, many children would be born in the future, both sons and daughters. These things I learned in Shoulianggou that are categorized as ‘ethnography’ have an uncanny quality which has attached itself to me, and has influenced my creativity since then.

Next I want to say something which has to do with art. You might say that my earliest effective study of artistic ‘theory’ and the establishment of my artistic aspirations were achieved on the mountain slopes facing Shoulianggou. There was a grove of apricot trees on the hillside, a sideline enterprise for the village. Looking after the apricot orchard was a job with the potential to annoy people intent on stealing the fruit, so the team sent me over to do it. Those summers the hillside became a paradise for me. Primarily because I didn’t eat a single apricot all day, making me satisfied by my self-control; and also because I could focus on appreciating the transformations of nature. Every day I would head up the hill with my paintbox and a book, but it wasn’t long before I ran out of books, so that one day all I could take was a copy of Mao’s Selected Works. I had memorized Mao’s best essays already, and was familiar with them to the point where I no longer thought about their meaning.

But the emotional effect and the benefit derived from reading the Selected Works that day under the apricot trees were of a kind rare in my experience, and the memory remains fresh in my mind. I read a splendid discourse on literature and art in an essay which had nothing to do with art:

Letting a hundred flowers blossom and a hundred schools of thought contend is the policy for promoting the progress of the arts and the sciences and a flourishing socialist culture in our land. Different forms and styles in art should develop freely and different schools in science should contend freely. We think that it is harmful to the growth of art and science if administrative measures are used to impose one particular style of art or school of thought and ban another. Questions of right or wrong in the arts and sciences should be settled through free discussion in artistic and scientific circles and through practical work in these fields. They should not be settled in summary fashion.(2)

As I reread it now, I really don’t know why I felt so moved by it; perhaps it was the discrepancy between this passage and the artistic environment of the day. Realization and indignation were mixed up in my emotional reaction: if Chairman Mao has defined the relationship so clearly, so rationally, what’s the matter with the workers in the fine arts right now! As I sat under the apricot trees, I read a few sentences, thought for a while, and looked around at the mountains, and pondered for the first time the great scope of the mission of art, its vast and resplendant meaning. The benefits gained from that day were buried in the heart of an amateur painter, and took a very important position there.

_______________

(2) Mao Zedong, ‘On the Correct Handling of Contradictions Among the People [February 27, 1957]’, Selected Readings from the Works of Mao Tse-tung (Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1971), pp. 432–79, qt. p. 462.

……

Out of Context

By Bei Dao

Translated by Theodore Huters

……

SIX

ON 8 January 1976 Zhou Enlai 周恩來 died. The news of his passing left a dark shadow and all sorts of rumours began to circulate. From the order of names published in the newspapers and reading between the lines people could make out the implications. Beginning at the end of March flower wreaths large and small filled Tiananmen Square, piling up like little mountains around the Monument to the People’s Heroes. The pine trees surrounding the square had been filled with white paper flowers.

Every day when I got off work I would get on the subway at its western terminus at Pingguo Yuan and go straight to Tiananmen Square. Walking through the vast sea of humanity there I for some reason felt my whole body covered in goose pimples, and looking at the poems that had been posted I impetuously felt like posting my own there as well, but couldn’t help feeling that I didn’t quite fit in.

The Qingming grave sweeping festival was on 4 April, which happened to be a Sunday, and the commemorative activities reached a crescendo. That morning I took the number 14 bus from home to Liubukou, from there following the crowd east all along Chang’an Boulevard, eventually arriving at the square. Mingling in the crowd I had a happy sense of anonymity and having disappeared, as well as of sharing this warm feeling with others—the happiness of being able to take my leave of personal choice in the name of the collective. I thought of Lenin’s words: ‘Revolution is the great holiday of the oppressed and exploited.’ Beneath the camouflage of the wreaths and white flowers, the square had an almost mystical feel of holiday about it. I looked all round: there were people standing on high ground giving speeches, to which everyone cheered and applauded; afterwards, as if by plan, the speakers were shielded and made to disappear into the crowd.

I went home to eat, but returned to the square after dinner. Taking advantage of the darkness, people became bolder. About nine I strolled over to the south-east corner of the Monument and suddenly heard a voice from out of the throng reading a denunciation out loud: ‘Jiang Qing 江青 is changing the direction of the “criticize Confucius and Lin Biao” movement so as to aim it at our beloved Premier Zhou …’ He stopped after reading one sentence, with those surrounding him repeating what he said in unison, the sound rippling out from the centre. To publically name Jiang Qing moved much further than writing poetic innuendo, and I was so agitated that I was trembling uncontrollably. As the dusk gathered I was firmly convinced that earth-shattering events were in the offing.

On Monday, 5 April I was quite distracted when I got to work; leaving work I saw Cao Yifan when I got home, only then learning how events had developed: that afternoon an angry crowd not only attacked the Great Hall of the People, but also overturned vehicles and burned the headquarters building of the workers in the square. That night news of the suppression circulated via non-official channels; it was said that batons had been used to kill numerous people, and the square had run with blood.

The next morning Shi Kangcheng rode his bicycle over to see me and Cao Yifan. With a dignified expression he knit his brow and said calmly that he had come to take his leave and entrust his girlfriend to our safekeeping—he was going to the square by himself to sit in meditation so as to express his resistance. To do that would be to court death, but at that juncture we were powerless to dissuade him. After he left I felt guilty: why had I not accompanied him in this time of national crisis? I acknowledged my inner cowardice and felt ashamed, but at the same time found a way to explain things to myself: ‘Heaven has endowed me with talent, so there must be a place to use it’—I needed to write more poetry and complete the revisions to Waves as quickly as possible. Because it was under a state of siege there was no way Shi Kangcheng could even get onto the square, so he returned from the bourn of death to the world of the living and the company of his girlfriend and the rest of us. Two months later I completed the revisions to the second draft of Waves.

……