Home / Renditions / Publications / Renditions Journal / No. 76

Renditions no. 76 (Autumn 2011)

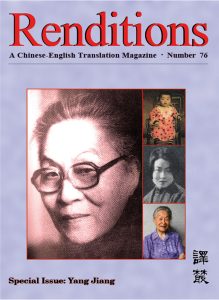

Special Issue: Yang Jiang

Guest Editor: Christopher G. Rea

In celebration of Yang Jiang’s centenary year, this special issue presents a sampling of works from Yang’s eight-decade-long career, including new translations of some of her best essays and short stories, as well as excerpts from her first play (Heart’s Desire, 1943), her memoirs, and her most recent book, Arriving at the Margins of Life: Answering My Own Questions (2007). Born during the year of the Republican Revolution, Yang Jiang (1911–2016) went on to distinguish herself as one of modern China’s most accomplished and versatile scholar-writers. Best known for her understated yet often humorous prose style, Yang is also an accomplished playwright and novelist; a prodigious translator from French, Spanish, and English; and an influential memoirist and intellectual who has come to be regarded by many as a paragon of modern Chinese humanism.

135 pages

Table of Contents

| SPECIAL ISSUE: YANG JIANG | ||

| Editor’s Page | 5 | |

| ‘To Thine Own Self Be True’: One Hundred Years of Yang Jiang

By Christopher G. Rea |

7 | |

| Heart’s Desire: Act I

Translated by Christopher G. Rea |

15 | |

| What a Joke

Translated by Christopher G. Rea |

34 | |

| On Qian Zhongshu and Fortress Besieged

Translated by Jesse Field |

68 | |

| My Translations

Translated by Judith M. Amory and Yaohua Shi |

98 | |

| We Three: Parts I and II

Translated by Jesse Field |

104 | |

| Arriving at the Margins of Life: Answering My Own Questions: Excerpt

Translated by Jesse Field |

130 | |

| Notes on Contributors | 135 | |

Sample Reading

The material displayed on this page is for researchers’ personal use only. If you wish to reprint it, please contact us.

Heart’s Desire: Act I

Translated by Christopher G. Rea

ACT I

(Setting: The parlour of ZHAO ZUYIN’s house, which is furnished in a refined, classical style. The furniture is all rosewood, calligraphic scroll paintings by famous hands adorn the walls, and the tables are laid out with antique porcelains. As the curtain rises, LI JUNYU, wearing a blue qipao, stands in the parlour. WANG SHENG stands to one side.)

LI JUNYU: Is this the Zhao residence?

WANG SHENG: Yes.

LI JUNYU: My surname is Li.

WANG SHENG: Li. OK, I got it.

LI JUNYU: I’m your master’s niece—Li Junyu.

WANG SHENG: I’ve never heard of you.

LI JUNYU: Isn’t this the Zhao residence? Isn’t your master Mr Zhao Zuyin?

WANG SHENG: Knowing his name isn’t going to help you. The master is a famous man—everyone’s heard of him!

LI JUNYU: I’m his niece. I just arrived from Beiping. Your master and mistress wrote me a letter asking me to come.

WANG SHENG: (Shaking his head) The master only has one niece, Third Mistress’s daughter, and her surname is Qian, not Li.

LI JUNYU: I’m your Fifth Mistress’s daughter. My surname’s Li, and I’ve always lived in Beiping.

WANG SHENG: I’ve never heard of any Fifth Mistress! Next you’re going to tell me there’s a Fifth Master!

LI JUNYU: Of course there is! My father was famous too, a great painter.

WANG SHENG: Oh? But he’s not one of us.

LI JUNYU: He recently passed away, and Fifth Mistress long before him. We’ve always lived in Beiping—you’d have no way of knowing. Go ask your master and mistress to come out. They’re expecting me.

WANG SHENG: Didn’t I tell you to wait here? The master and mistress aren’t up yet! I’d really be asking for it to disturb them so early on a Sunday.

LI JUNYU: In that case, help me carry my trunk in.

WANG SHENG: You can’t bring it in here. The weight of it will ruin the carpet.

LI JUNYU: But someone will steal it if I leave it at the door.

WANG SHENG: Don’t you have someone watching it for you?

LI JUNYU: (To offstage) Binru, Binru! We’ll carry it in ourselves.

(Exit LI JUNYU, who then re-enters carrying a trunk and a mesh basket together with CHEN BINRU, who is dressed in an old, tattered, blue Chinese full-length cotton gown. WANG holds CHEN back, but CHEN pushes him aside and places the trunk and the basket in the centre of the parlour. CHEN exits and then re-enters carrying a rush bag and two wooden boards, tied together.)

WANG SHENG: (Stands to the side with his arms crossed) Great, great—a fine world of bandits this has turned into! The gentleman speaks with his mouth, not with his fists.

CHEN BINRU: A rascal like you only understands when fists do the talking!

WANG SHENG: (With his arms crossed in front of his chest) I’m not going to fight you.

CHEN BINRU: You wouldn’t dare!

LI JUNYU: Binru, just ignore him! Everything’s here. (Counts the luggage.)

(Exit WANG SHENG.)

……We Three: Part I

Translated by Jesse Field

Part I: We Two Grow Old

One night, I had a dream. Zhongshu and I were out on a walk together, talking and laughing, when we came to a place we did not know. The sun had set behind the mountains, and dusk was approaching. Then Zhongshu disappeared into the void. I searched everywhere but could find no trace of him. I called to him, but there was no answer. It was just me, alone, standing there in the wasteland not knowing where Zhongshu had gone. I cried out to him, calling his full name, but my cries just fell into the wilderness without the faintest echo, as if they’d been swallowed. Complete silence added to the blackness of the night, deepening my loneliness and sense of desolation. In the distance, I saw only layer upon layer of dusky dark. I was on a sandy road with a forest to one side. There was a murmuring brook; I couldn’t see how wide it was. When I turned to look back, I saw what appeared to be a cluster of houses. It was an inhabited place, but since I couldn’t see any lights, I thought they must be quite far away. Had Zhongshu gone home on his own? Then I’d better go home too! Just as I was looking for the way back, an old man appeared, pulling an empty rickshaw. I hurried over to bar his way, and sure enough he stopped, but I couldn’t tell him where I wanted to go. In the midst of my desperation, I woke up. Zhongshu lay next to me in bed, sound asleep.

I tossed and turned for the rest of the night, waiting for Zhongshu to wake up; then I told him about what happened in my dream. I reproached him: How could you have abandoned me like that, leaving on your own without a word to me? Zhongshu didn’t try to defend the Zhongshu of my dream. He only consoled me by saying: this is an old person’s dream. He often had it too.

Yes, I’ve had this sort of dream many times. The setting may differ, but the feeling is the same. Most often the two of us emerge from some place, then, in the blink of an eye, he’s gone. I ask after him everywhere, but nobody pays any attention to me. Sometimes I search for him everywhere but end up in a succession of alleys, all with dead ends. Sometimes I am alone in a dimly lit station, waiting for the last train, but the train never comes. In every dream I am lonely and desperate. If only I could find him, I think, we could go home together.

Zhongshu probably remembered my reproach, and caused this dream to be ten thousand miles long.

……