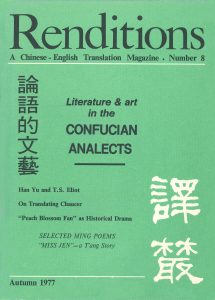

Home / Renditions / Publications / Renditions Journal / No. 8

Renditions no. 8 (Autumn 1977)

161 pages

Table of Contents

(*Asterisks denote items with Chinese text)

| Editor’s Page | 4 | |

| Articles | ||

| Vincent Y. C. Shih | Literature and Art in The Analects Translated by C. Y. Hsu | 5 |

| Charles Hartman | Han Yü and T.S. Eliot—A Sinological Essay in Comparative Literature | 59 |

| Essays | ||

| Han Yü | Selected Essays* Translated by Shih Shun Liu | |

| I. The Thousand-li Horse | ||

| II. On the Teacher | ||

| III. Biography of Wang Ch’eng-fu, the Mason | ||

| Chin Chun-ming | Four Episodes in Praise of the Orchid* Translated by Yuan Heh-hsiang | 92 |

| Fang Pao | Tso Kuang-tou and Shih K’o-fa* Translated by Wen-djang Chu | 97 |

| Art of Translation | ||

| Mimi Chan | On Translating Chaucer into Chinese | 39 |

| Fiction | ||

| Shen Chi-chi | Miss Jen* Translated by Frederick C. Tsai | 52 |

| Ting Ling | In the Hospital Translated by Susan M. Vacca | 123 |

| Wang Ting-chun | The Wailing Chamber Translated by Simon S. C. Chau | 137 |

| Drama | ||

| Lynn A. Struve | The Peach Blossom Fan as Historical Drama | 99 |

| K’ung Shang-jen | The Peach Blossom Fan* Translated by Richard E. Strassberg | 115 |

| Poetry | ||

| Daniel Bryant | Three Varied Centuries of Verse—a brief note on Ming poetry | 82 |

| ———— | Selected Ming Poems Translated by Daniel Bryant | 85 |

| Art | ||

| Han Kan (attributed) | Two Horses and a Groom | 78 |

| Jen Po-nien | Seeking Inspiration on the Donkey’s Back | 149 |

| Briefs | ||

| ———— | A Race Without Winners, “Picture” in the Mind | 96 |

| ———— | Cardinal Principle of Translation | 136 |

| ———— | Books Received | 157 |

| Notes on Contributors | 147 | |

| Chinese Texts | 149 | |

| Index to Renditions Volumes III and IV (Nos. 6, 7 and 8) | 158 | |

Sample Reading

The material displayed on this page is for researchers’ personal use only. If you wish to reprint it, please contact us.

On the Teacher

By Han Yu

Translated by Shih Shun Liu

IN ANCIENT TIMES scholars always had teachers. It takes a teacher to transmit the Way, impart knowledge and resolve doubts. Since man is not born with knowledge, who can be without doubt? But doubt will never be resolved without a teacher.

He who was born before me learned the Way before me, and I take him as my teacher. But if he who was born after me learned the Way before me, I also take him as my teacher. I take the Way as my teacher. Why should I care whether a man was born before or after me? Irrespective therefore of the distinction between the high-born and the lowly, and between age and youth, where the Way is, there is my teacher.

Alas, it has been a long time since the Way of the teacher was transmitted! And so it is difficult to expect people to be without doubt. Though ancient sages far surpassed the common folk, they nevertheless asked questions of their teachers. On the other hand, the masses of today, who are far inferior to the sages, are ashamed to learn from their teachers. Consequently, the sage became more sage, and the ignorant more ignorant. Indeed, is this not the reason why the sages were sage and the ignorant folk ignorant?

He who loves his son selects a teacher for the child’s education, but he is ashamed to learn from a teacher himself. He is indeed deluded. The teacher of a child is one who gives instruction on books and on the punctuation of sentences. This is not what I meant when I talked about one who transmits the Way and resolves doubts. To take a teacher for instruction in correct punctuation and not to take a teacher to help resolve doubts is to learn the unimportant and leave out the important. I do not see the wisdom of it.

Shamans, doctors, musicians and craftsmen are not ashamed to take one another as teachers. But, when the scholar-officials speak of teachers and pupils, there are those who get together and laugh at them. When questioned, their reply is that so and so is of the same age as so and so and that their understand- ing of the Way is similar. If one takes another who holds a low position as his teacher, it is something to be ashamed of. If it is some high official who is taken as a teacher, it is a form of flattery. Alas, the Way of the teacher is no longer understood! Shamans, doctors, musicians and craftsmen are not respected by a gentleman, but their wisdom is beyond that of the gentleman. Is this not strange?

Our sages had no constant teachers. Confucius took T’an-tzu, Ch’ang-hung, Shih-hsiang and Lao-tan as his teachers, all of whom were not so wise as himself. Said Confucius, “Among three men who walk with me, there must be a teacher of mine”. The pupil is therefore not necessarily inferior to the teacher, and the teacher is not necessarily wiser than the pupil. What makes the difference is that one has heard the Way before the other and that one is more specialized in his craft and trade than the other—that is all.

Li P’an, who is seventeen, is fond of ancient literature and is deeply versed in the six arts, the classics and chronicles. Not subject to the trend of the day, he has studied under me. Pleased that he can practice the ancient Way, I have written this essay on the teacher to present to him.