Home / Renditions / Publications / Renditions Journal / Nos. 59 & 60

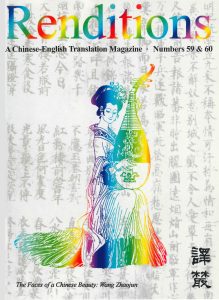

Renditions nos. 59 & 60 (Spring & Autumn 2003)

The Faces of a Chinese Beauty: Wang Zhaojun

Wang Zhaojun was a Han court lady who volunteered to marry the Xiongnu Khan in 33 BC. Her plight, and her place as one of the four great beauties of China, have fascinated poets, playwrights, painters, and politicians for two thousand years. She has been portrayed by generations of writers as pitiable, courageous, wise, or patriotic, though such depictions reveal more about the authors than about Wang herself.

The most representative of the poems, plays, stories and paintings celebrating this beauty are featured in this special double issue. In these pages the reader will find a broad spectrum of Chinese cultural attitudes and perceptions of women through the centuries.

268 pages

Table of Contents

| Editor’s Page | 5 | |

| Eva Hung | Wang Zhaojun: from History to Legend | 7 |

| POETRY | ||

| Shi Cong | The Words of Wang Mingjun, with Preface

Translated by Burton Watson |

28 |

| Bao Zhao | Wang Zhaojun

Translated by Jam Ismail and Tam Pak Shan |

32 |

| Shen Manyuan | Zhaojun’s Regret

Translated by Maureen Robertson |

34 |

| Yu Xin | Song of Zhaojun, Composed by Imperial Command

Translated by Eva Hung |

36 |

| Lady Hou | Setting My Feelings Free

Translated by Carolyn Ford |

38 |

| Li Bai | Wang Zhaojun

Translated by Julie Landau |

40 |

| Du Fu | Thoughts on an Ancient Site III

Translated by David Lunde |

42 |

| Rong Yu | Marriage to the Barbarians

Translated by David E. Pollard |

44 |

| Bai Juyi | Wang Zhaojun (two poems)

Translated by Burton Watson |

46 |

| Su Yu | On the Policy of Giving a Bride to Cement the Peace

Translated by Julie Landau |

50 |

| Wang Rui | Why Grieve, Zhaojun?

Translated by Audrey Heijns and David Lunde |

52 |

| Hu Zeng | The Han Palace

Translated by Haun Saussy |

54 |

| Chu Guangxi | Wang Zhaojun

Translated by Julie Landau |

56 |

| Liang Qiong | Zhaojun’s Complaint

Translated by Maureen Robertson |

58 |

| Wang Anshi | Songs of the Luminous Lady: two poems

Translated by Eva Hung |

59 |

| Ouyang Xiu | Reply to Wang Anshi’s Poem on the Luminous Lady (No. 2)

Translated by John Dent-Young |

64 |

| Sima Guang | Reply to ‘Song of the Luminous Lady’ by Wang Anshi

Translated by Jianqing Zheng and Margo Stever |

66 |

| Su Shi | Zhaojun Village

Translated by Jam Ismail and Tam Pak Shan |

68 |

| Lu Benzhong | Bright Consort

Translated by David E. Pollard |

70 |

| Lu You | Song of the Bright Consort

Translated by Jane Lai |

72 |

| Wang Shipeng | Zhaojun’s Home Village

Translated by Jane Lai |

74 |

| Huang Wenlei | Ballad of Zhaojun

Translated by David E. Pollard |

76 |

| Wang Yun | Painting of Wang Zhaojun Going Out the Border Passes(first of two poems)

Translated by Jane Lai |

80 |

| Ma Zhiyuan | To the Tune ‘Purple Fungus Route’

Translated by David E. Pollard |

82 |

| Yu Ji | On the Painting ‘Zhaojun Leaves the Country’

Translated by John Dent-Young |

84 |

| Zhang Zhu | To the Tune ‘Grief of Zhaojun’

Translated by Audrey Heijns and David Lunde |

86 |

| Zhang Kejiu | Inspired by Illustration of Zhaojun Leaving for the Frontier (To the Yue Tune of ‘Zhaier ling’)

Translated by Ian Chapman |

88 |

| Peng Hua | Song of the Luminous Lady

Translated by Jianqing Zheng and Margo Stever |

90 |

| Qiu Jin | On a Portrait of Zhaojun

Translated by John Dent-Young |

92 |

| Wang Xun | Lady Luminous

Translated by Jam Ismail and Tam Pak Shan |

94 |

| Huang Youzao | Inscribed on a Painting of the Bright Consort Passing Beyond the Border

Translated by Maureen Robertson |

96 |

| Cai Daoxian | A Vindication of Wang Qiang and Mao the Painter

Translated by Haun Saussy |

98 |

| Wei Cheng | Wang Zhaojun

Translated by John Dent-Young |

100 |

| Xia Wanchun | The Bright Consort

Translated by David E. Pollard |

102 |

| Qi Jiguang | Song of the Bright Consrt

Translated by David E. Pollard |

104 |

| Hu Xiake | Wang Zhaojun Series (No. 3)

Translated by Eva Hung |

106 |

| Liu Xianting | Wang Zhaojun (No. 2)

Translated by David Bryant |

108 |

| Ge Yi | Zhaojun

Translated by Maureen Robertson |

110 |

| Yan Guangmin | Song of Zhaojun

Translated by Eva Hung |

112 |

| Huang Zhijun | A Eulogy

Translated by Eva Hung |

114 |

| Yuan Mei | Song of the Fair Consort

Translated by David E. Pollard |

116 |

| Li Hanzhang | On a Painting of the Bright Consort Passing Beyond the Border

Translated by Maureen Robertson |

118 |

| Guo Shuyu | Bright Consort

Translated by Maureen Robertson |

122 |

| Wang Lingwen | Zhaojun’s Complaint

Translated by Maureen Robertson |

123 |

| Xu Deyin | Passing Beyond the Border

Translated by Maureen Robertson |

124 |

| Bao Guixing | The Luminous Lady

Translated by Eva Hung |

126 |

| Sheng Yin | Ballad of Greengrave

Translated by Daniel Bryant |

128 |

| Zhou Xiumei | Zhaojun

Translated by Carolyn Ford |

132 |

| TALE AND BIOGRAPHY | ||

| Anonymous | Wang Zhaojun bianwen: excerpts

Translated by Eugene Eoyang |

136 |

| Hu Shi | Wang Zhaojun: Patriotic Heroine of China

Translated by Janice Wickeri |

145 |

| DRAMA | ||

| Xue Dan | Zhaojun’s Dream

Translated by Mark Stevenson and Wu Cuncun |

154 |

| Chen Yujiao | Lady Zhaojun Crosses the Frontier

Translated by Elizabeth Wichmann-Walczak and Fan Xing |

181 |

| Guo Moruo | Wang Zhaojun: Act II

Translated by T.M. McClellan |

195 |

| Gu Qinghai | Zhaojun: Act III

Translated by David E. Pollard |

211 |

| Cao Yu | The Consort of Peace: Act V

Translated by Monica Lai |

221 |

| Ma Shizheng | Theme Song from Zhaojun Crossing the Frontiers

Translated by Rupert Chan |

255 |

| Notes on Contributors | 251 | |

| Book Notices | 268 | |

Sample Reading

The material displayed on this page is for researchers’ personal use only. If you wish to reprint it, please contact us.

Wang Zhaojun (two poems)

By Bai Juyi

Translated by Burton Watson

I

Full in her face, barbarian sands, wind full in her hair;

gone from eyebrows, the last traces of kohl, gone the rough from cheeks:

hardship and grieving have wasted it away—

now indeed it is the face in the painting!

II

As the Han envoy departs, she gives him these words:

‘When will they send the yellow gold to ransom me?

Should the Sovereign ask how I look,

don’t say I’m any different from those palace days!’

白居易:王昭君

(一)

滿面胡沙滿鬢風

眉銷殊黛臉銷紅

愁苦辛勤憔悴盡

如今卻似畫圖中

(二)

漢使卻回憑寄語

黃金何日贖娥眉

君王若問妾顏色

莫道不如宮裏時

Bright Consort

By Guo Shuyu

Translated by Maureen Robertson

When at last she took up her lute

And travelled beyond the border,

It had nothing to do with a portrait

That wronged her realm-shaking beauty.

Imperial Han pursued a policy of peace

Through marriage with the western tribes;

Better by far than sending forth troops,

By the thousands, to guard the frontier.

郭漱玉:明妃

竟把琵琶塞外行

非關圖畫誤傾城

漢家議就和戎策

差勝防邊十萬兵

Wang Zhaojun: Patriotic Heroine of China

By Hu Shi

Translated by Janice Wickeri

READERS of this biography will, for a certainty, find it odd that the name ‘Wang Zhaojun’ is here joined to the phrase ‘patriotic heroine’. Wasn’t Wang Zhaojun the Han dynasty court lady who found no favour with the emperor? It was she, was it not, who suffered at the hand of the court painter Mao Yanshou, failed to catch the fancy of Emperor Yuan and was then sent to pacify the barbarians? How could she be considered a patriotic heroine? Readers, your doubts are not without foundation, but you’ve been hoodwinked for thousands of years by those ancients who wrote the books, and you repeat the story even to this day. The simple fact is that this patriotic heroine, Wang Zhaojun, has been done 2,000 years of injustice, neglected right up to the present. Since I have now found conclusive evidence to prove that Wang Zhaojun was indeed a national heroine, I dare not but commend her to you, that you may all worship at her altar. And this is the reason I wrote the biography that follows.

First, the old version, which has it that Wang Zhaojun was a court lady to Emperor Yuan of the Han dynasty. In those days, there were simply too many in the women’s quarters; one couldn’t get to know them all in a short while. Thereupon, a number of artists were summoned to put the likenesses of all the palace ladies into an illustrated manual, making it easy for the emperor to look at the person’s likeness in the book and summon her to his presence by picture.

sired. Emperor Yuan’s heart lay heavy within him, but he had promised the Xiongnu Khan and it wouldn’t do to break one’s word to a barbarian. He could do nothing but give Zhaojun to the Xiongnu. Afterwards, the more Emperor Yuan thought on it, the greater pity it seemed, and he had all the painters rounded up and executed.

Thus the tale of Wang Zhaojun as it used to be told. Imagine the colossal nerve of those painters, presuming to flog their wares in the very palace of the emperor. Besides, once Emperor Yuan had a look at Zhaojun, why on earth didn’t he find somebody else to take her place? This story is not to be relied upon. The evidence I’ve mustered comes from the old books, too, so it’s not baseless nonsense. Lend your ears, then, to my tale.

Wang Zhaojun, named Qiang, was a native of Zigui in Shu County. Her father was Wang Rang; Zhaojun was his only child. From childhood, Zhaojun was different from other little girls. Her every move and gesture were in accordance with the rules of etiquette. She grew into a woman of both outer beauty and inner intelligence, peerless in grace and charm. She was just as the writer Song Yu put it: ‘A soupçon more would be excessive; a tad less too little. Powder would make her too pale and rouge too rosy.’ On top of this, she was gentle, chaste; so much so that before she turned seventeen, she was famous throughout the land. When she put up her hair and became a woman, the scions of gentry and kings came in droves to seek her hand. But her father could never bring himself to grant his permission. It chanced that Emperor Yuan was then choosing ladies for his court. When Wang Rang heard this news, he sought his daughter out to tell her of his wish to send her to the palace. When Wang Zhaojun heard this and weighed it up in her own heart, she thought to herself that her father had only one daughter and, as the old saying aptly puts it, ‘When one has a daughter and no son, he has nothing to fall back on in an emergency.’ Since mother and father had only me, how can I just leave my debt to them unpaid? I may as well take this opportunity to go into the palace. Perhaps I’ll capture the favour of the Son of Heaven and be granted a fairly high rank, like Zhaoyi or Jieyu. Wouldn’t this bring glory upon my parents and all my ancestors? Then my parents won’t have given birth to me in vain. Her mind was made up and she eagerly to Wang Rang’s idea. Seeing that she was willing, Wang Rang presented his daughter to the palace.

You should realize, Readers, that Zhaojun had acted out of filial piety, desirous of being a daughter who brought honour upon her house. How was she to know that the depths of the emperor’s palace were a most wretched and piteous place, a place of which scores of poets, since ancient times, had written scores of poetic ‘palace laments’, long ago exhausting the possibilities of the form? And then there’s The Story of the Stone where the imperial concubine, Jia Yuanchun spoke to her father of ‘that day you sent me away where no one gets to see me’. That phrase, how mournfully it’s put. If no one sees you, it goes without saying that any joy in life is gone.

Each and every one of the several thousand ladies in the harem is on the alert; they keep watching out for the emperor’s approach, even going so far as to set bamboo leaves across the doorway and scatter salt water over the ground to attract the goats pulling his cart. In truth, however good a person you may be, once you are in this place, how can you hope to catch the Son of Heaven’s gaze, if not by foul and improper currying of favour? Ah, how could our patriotic heroine, Wang Zhaojun, bring herself to stoop to such sordid and despicable actions as these?

……