Home / Renditions / Publications / Renditions Journal / No. 26

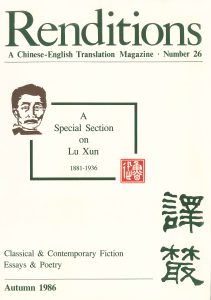

Renditions no. 26 (Autumn 1986)

Featuring works from Lu Xun’s early and late periods. Paintings by Qiu Sha inspired by Lu Xun’s sayings are included.

166 pages

Table of Contents

| Editor’s Page | 4 | |

| ART | ||

| Huang Yongyu | Selections from A Can of Worms Translated by Geremie Barmé | 11 |

| ESSAYS | ||

| Zhou Zuoren | Seven Essays Translated by D. E. Pollard, Don J. Cohn & Richard Rigby | 68 |

| The Ageing of Ghosts | ||

| In Praise of Mutes | ||

| On “Passing the Itch” | ||

| Reading on the Toilet | ||

| Japan and China | ||

| The Chinese National Character — A Japanese View | ||

| Japan Re-encountered | ||

| FICTION | ||

| Wan Zhi | The Clock Translated by Bonnie S. McDougall & Kam Louie | 7 |

| Feng Menglong | Xingshi Hengyan: How Hailing of the Jurchens was Destroyed through Unbridled Lust Translated by Copal Sukhu | 22 |

| POETRY | ||

| Lu You | 31 Quatrains Translated by C. H. Kwock & V. McHugh | 51 |

| SPECIAL SECTION ON LU XUN | ||

| Lu Xun | Toward a Refutation of the Voices of Evil Translated by J. E. Kowallis | 108 |

| ———— | The World of Lu Xun Paintings by Qiu Sha & Wang Weijun | 120 |

| Lu Xun | Confucius in Modern China Translated by D. E. Pollard | 125 |

| Lu Xun | Selected Classical Poems Translated by J. E. Kowallis | 132 |

| Lu Xun | Wild Grass Translated by Ng Mau-sang | 151 |

| Notes on Contributors | 165 | |

Sample Reading

The material displayed on this page is for researchers’ personal use only. If you wish to reprint it, please contact us.

The Chinese National Character—A Japanese View

By Zhou Zuoren

Translated by Richard Rigby

Yasuoka Hideo, in his The Chinese National Character as Seen in the Novel, published this April [ 1926] by Shuhokaku in Tokyo, sets out in ten chapters the inherently evil characteristics of the Chinese people as evidenced in the novels of the Yuan, Ming and Qing dynasties, and subjects these characterstics to mockery and abuse. I fully acknowledge the existence of all the failings of which the author accuses the Chinese. The Han race does indeed deserve extinction, and its lack of progress and self-improvement are absolutely incontrovertible facts. For proof of this there is no need to search as far back as the novels of four or five centuries ago: the reality daily assaulting our eyes and ears provides ample and inescapable evidence of cowardice, cruelty, licentiousness, obscurantism and untruthfulness. Not even the most eloquent “nationalist” could offer a convincing defence, and his best efforts would only result in the addition of arrogance and vanity to this catalogue. If this is human nature, then the Chinese is man at his most representa- tive, and the rest of the world shall be at his mercy. If, however, this is not so, and there is no room for the survival of the heartless, the foolish and the cowardly, then China’s continued existence contradicts the very laws of heaven. One might go so far as to say that even were the nation to perish, its crimes would still not be expunged completely! I know not what hallucinogenic potion the Chinese have swallowed in recent times which has induced in them the belief that the so-called culture and ethical code of the East somehow entitles them to lord it over the rest of the world. Fantastic as this may seem, at this very moment they are making a great song and dance about it! Yasuoka’s book should be translated and a copy given to everyone of them, so that they can see how their honourable features really appear, and then judge for themselves whether or not they are good enough to be anything but slaves.

And yet I do not like to see a Japanese writing such a book. I certainly do not mean that China’s faults should only be exposed by the Chinese; nor do I mean to suggest that Japan has no serious faults of its own. No, what makes me unhappy is the attitude displayed by the “China experts”, which certainly does not redound to Japan’s credit. We know that, if the truth be told, contemporary Greece has somewhat degenerated; but the nations of Europe and the Americas refrain from caustic sarcasm and abuse, out of consideration for the blessings of that ancient culture which have been bestowed upon them. Even if they do record the sad facts, they do so dispassionately, without discrediting their own character.

I have on the desk in front of me a copy of the American Professor Hart’s Greek Religion and its Legacy, a volume from the series Our Debt to Greece and Rome, and seeing it I cannot but be struck by the great difference between the breadth of mind of the Japanese and Westerners. We have no right whatsoever to present ourselves to the Japanese in the guise of creditors: on the contrary, for my part I believe that in some ways we have done them wrong—the influence ofConfucianism, for instance, has done no little harm to the peoples of Japan, Korea and Annam. But from the viewpoint of Japan, China does indeed stand in a position somewhat analogous to that of Greece to Rome. Japan certainly cannot dismiss the influence of China as one would a passing stranger. Seeing the level to which China has now fallen, it is only proper that Japan should feel deep sorrow, but unrestrained glee or amusement hardly seem the appropriate emotions. We do not wish Japan to praise or to defend China. We hope, rather, for her honest and severe admonition, and even her reprimands. But the flippant and vulgar attitude of the “China experts” should be dispensed with if at all possible. Because I deeply admire Japanese culture, I hope that this flippancy will not become one of Japan’s national characteristics.